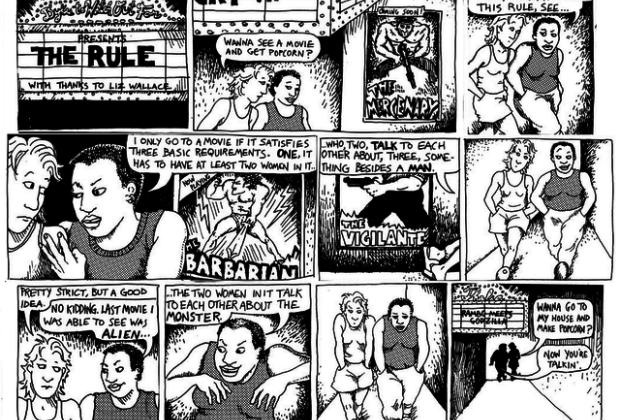

The Bechdel Test is simple. Originally devised by Liz Wallace, popularized in comic form in 1985 by Alison Bechdel, it asks three questions about a work of fiction:

- Does it have at least two female characters?

- Who talk to each other?

- About something other than a man?

To pass, the answer to all three questions has to be “yes”. Many people have added various caveats to the test: they have to be two named female characters, the conversation has to take at least 20/30/60 seconds, the conversation can’t be about marriage, romance or babies…

The test isn’t a “test of feminism”. To begin with, whether a work is feminist is a complex matter, requiring so much more than answering three questions. Rather, the purpose of the Bechdel Test is to determine trends, and it best accomplishes this when compared to the Reverse Bechdel Test: Does the work have two male characters, who talk to each other, about something other than a woman?

Most films pass the Reverse Bechdel test – it’s a genuine struggle to find one that doesn’t. But the list of films failing the Bechdel Test is embarrassing. None of the Star Wars films pass, None of the Lord of the Rings films pass. Only a handful of Pixar films pass. None of the Die Hard, Back to the Future, or (if you add the “twenty second” rule) Harry Potter films pass.

Again, passing the test doesn’t make a film inherently pro-women, and failing it doesn’t mean its a travesty of feminism – my favorite film, Misery, fails, whereas The Room passes with flying colours, and Misery has one of the best-written female characters in movie history. (The Room does not.)

If films failed both tests equally, we could agree that there’s no problem. But when half the films ever made fail the Bechdel Test, with barely any failing its counterpart, it’s hard to deny that there’s something wrong.

And so, this column will be looking at comedy films, and asking firstly whether they pass the Bechdel Test, but more importantly: How does this film portray women, if at all? Do they exist solely as lovers or mothers, or do they have opinions and needs of their own? Are they three-dimensional characters, or stereotypes solely there to support men?

Women, it was recently discovered, are people. Let’s find out if comedy films treat them that way.

(Originally posted January 31st, 2014 at Illegitimate Theatre.)

Hello! I simply would like to give a huge thumbs up for the nice information you have here on this post. I will probably be coming back to your weblog for more soon.

you’ve a fantastic blog right here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

It抯 onerous to search out knowledgeable folks on this topic, however you sound like you recognize what you抮e speaking about! Thanks

There are some fascinating points in time in this article however I don抰 know if I see all of them heart to heart. There is some validity but I’ll take hold opinion till I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we wish more! Added to FeedBurner as nicely

I抎 must check with you here. Which is not one thing I normally do! I get pleasure from studying a publish that may make individuals think. Also, thanks for permitting me to remark!

An interesting dialogue is value comment. I feel that it is best to write extra on this subject, it won’t be a taboo topic but typically persons are not sufficient to speak on such topics. To the next. Cheers

Hey! I simply want to give a huge thumbs up for the nice data you have right here on this post. I will be coming again to your blog for extra soon.

I happen to be writing to let you know what a great experience my cousin’s daughter enjoyed viewing your site. She picked up a wide variety of details, including what it’s like to possess an awesome coaching mindset to let other individuals just grasp chosen very confusing issues. You really surpassed her desires. I appreciate you for coming up with these insightful, healthy, explanatory as well as unique tips on that topic to Jane.

You made some first rate factors there. I looked on the internet for the difficulty and found most people will associate with along with your website.

A formidable share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing a bit of analysis on this. And he in reality bought me breakfast as a result of I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the deal with! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to debate this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If doable, as you grow to be experience, would you thoughts updating your blog with more particulars? It is highly useful for me. Massive thumb up for this blog submit!

After research a number of of the blog posts on your website now, and I really like your method of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking again soon. Pls take a look at my website as properly and let me know what you think.

It抯 onerous to seek out knowledgeable people on this subject, but you sound like you recognize what you抮e speaking about! Thanks

I抦 impressed, I must say. Really not often do I encounter a weblog that抯 each educative and entertaining, and let me let you know, you could have hit the nail on the head. Your concept is excellent; the issue is one thing that not enough individuals are talking intelligently about. I’m very completely satisfied that I stumbled across this in my search for one thing regarding this.

There are certainly numerous details like that to take into consideration. That may be a nice level to convey up. I supply the ideas above as general inspiration however clearly there are questions like the one you carry up where crucial factor can be working in trustworthy good faith. I don?t know if best practices have emerged around issues like that, but I am sure that your job is clearly recognized as a fair game. Both boys and girls feel the impact of just a moment抯 pleasure, for the rest of their lives.

Would you be inquisitive about exchanging hyperlinks?

This site is mostly a stroll-by means of for all of the information you wished about this and didn抰 know who to ask. Glimpse right here, and also you抣l undoubtedly discover it.

A formidable share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing somewhat analysis on this. And he in actual fact bought me breakfast as a result of I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! However yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I really feel strongly about it and love studying extra on this topic. If attainable, as you turn out to be expertise, would you thoughts updating your blog with extra details? It’s extremely helpful for me. Large thumb up for this weblog post!

This actually answered my drawback, thank you!

Your house is valueble for me. Thanks!?

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read something like this before. So nice to seek out anyone with some unique ideas on this subject. realy thank you for starting this up. this web site is one thing that is needed on the net, somebody with a little originality. useful job for bringing one thing new to the web!

I used to be very happy to seek out this net-site.I wanted to thanks on your time for this glorious read!! I definitely having fun with each little little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you weblog post.

Would you be concerned with exchanging hyperlinks?

It’s best to participate in a contest for among the finest blogs on the web. I will suggest this web site!

Would you be keen on exchanging hyperlinks?

very nice submit, i definitely love this web site, carry on it

I抦 impressed, I need to say. Really hardly ever do I encounter a blog that抯 both educative and entertaining, and let me let you know, you’ve got hit the nail on the head. Your thought is outstanding; the problem is one thing that not sufficient people are talking intelligently about. I’m very completely happy that I stumbled across this in my search for one thing regarding this.

I am commenting to make you be aware of what a really good experience my girl enjoyed reading through your web site. She learned too many issues, most notably how it is like to have a wonderful helping style to have other individuals with no trouble fully understand certain tricky subject areas. You truly did more than her expected results. Many thanks for producing those helpful, safe, edifying and also fun tips on your topic to Tanya.

A formidable share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing somewhat analysis on this. And he in fact purchased me breakfast as a result of I discovered it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! However yeah Thnkx for spending the time to debate this, I really feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If possible, as you grow to be experience, would you mind updating your blog with more details? It is highly helpful for me. Massive thumb up for this weblog publish!

After study a couple of of the weblog posts in your website now, and I actually like your method of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site listing and shall be checking again soon. Pls try my web site as effectively and let me know what you think.

Hiya! I simply wish to give a huge thumbs up for the great information you’ve got here on this post. I can be coming back to your blog for more soon.

Once I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any method you can take away me from that service? Thanks!

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..extra wait .. ?

Would you be concerned about exchanging hyperlinks?

I’m often to blogging and i really respect your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your website and hold checking for brand new information.

I and also my pals have been analyzing the excellent tips located on the website and so quickly got an awful suspicion I had not thanked the web site owner for those techniques. My boys had been totally very interested to see all of them and have now surely been using them. Many thanks for actually being very accommodating and then for pick out such fabulous subjects millions of individuals are really desperate to be informed on. My honest apologies for not expressing gratitude to sooner.

Oh my goodness! an amazing article dude. Thanks Nonetheless I’m experiencing problem with ur rss . Don抰 know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone getting identical rss drawback? Anyone who is aware of kindly respond. Thnkx

I抦 impressed, I must say. Really rarely do I encounter a weblog that抯 each educative and entertaining, and let me tell you, you may have hit the nail on the head. Your idea is excellent; the problem is one thing that not enough people are talking intelligently about. I am very completely happy that I stumbled throughout this in my seek for one thing regarding this.

I found your blog website on google and check just a few of your early posts. Proceed to maintain up the very good operate. I simply further up your RSS feed to my MSN News Reader. Searching for ahead to reading more from you in a while!?

I was more than happy to find this web-site.I wished to thanks on your time for this wonderful learn!! I undoubtedly having fun with each little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to take a look at new stuff you weblog post.

Hiya! I simply would like to give an enormous thumbs up for the great info you may have right here on this post. I can be coming again to your weblog for extra soon.

After examine a number of of the weblog posts in your website now, and I really like your approach of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site list and will likely be checking again soon. Pls check out my website as properly and let me know what you think.

After research a number of of the weblog posts on your web site now, and I actually like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website listing and shall be checking back soon. Pls take a look at my website as properly and let me know what you think.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read anything like this before. So nice to search out somebody with some original ideas on this subject. realy thanks for beginning this up. this website is one thing that’s wanted on the web, someone with a bit of originality. helpful job for bringing something new to the web!

you will have a great weblog right here! would you wish to make some invite posts on my weblog?

This actually answered my problem, thank you!

I抦 impressed, I have to say. Actually rarely do I encounter a blog that抯 each educative and entertaining, and let me inform you, you’ve got hit the nail on the head. Your thought is excellent; the issue is something that not enough people are talking intelligently about. I’m very joyful that I stumbled throughout this in my search for one thing regarding this.

I’m often to blogging and i actually appreciate your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your web site and keep checking for brand spanking new information.

There are some interesting deadlines on this article but I don抰 know if I see all of them middle to heart. There is some validity however I will take hold opinion till I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like more! Added to FeedBurner as effectively

This actually answered my problem, thanks!

I found your weblog site on google and examine just a few of your early posts. Proceed to maintain up the excellent operate. I just extra up your RSS feed to my MSN Information Reader. In search of forward to reading extra from you afterward!?

An interesting discussion is value comment. I think that you need to write more on this topic, it might not be a taboo subject however generally individuals are not enough to talk on such topics. To the next. Cheers

Once I initially commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a remark is added I get 4 emails with the same comment. Is there any approach you possibly can remove me from that service? Thanks!

There are some attention-grabbing deadlines in this article but I don抰 know if I see all of them center to heart. There’s some validity however I’ll take hold opinion until I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like extra! Added to FeedBurner as well

This is the proper blog for anyone who desires to search out out about this topic. You realize so much its virtually hard to argue with you (not that I truly would want匟aHa). You positively put a brand new spin on a subject thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, just nice!

This actually answered my drawback, thank you!

Hi there! I just would like to give a huge thumbs up for the great information you’ve gotten here on this post. I will probably be coming back to your weblog for more soon.

I want to express thanks to you for rescuing me from this type of trouble. As a result of surfing around through the world-wide-web and coming across concepts which were not powerful, I believed my life was done. Living without the presence of approaches to the difficulties you have solved by means of your blog post is a crucial case, as well as the ones which might have badly damaged my career if I hadn’t noticed your website. Your main expertise and kindness in handling all the stuff was very useful. I am not sure what I would have done if I hadn’t come across such a thing like this. I can at this moment relish my future. Thanks a lot so much for your specialized and results-oriented guide. I won’t hesitate to propose the website to anyone who needs and wants support about this issue.

Someone essentially help to make seriously articles I would state. This is the first time I frequented your web page and thus far? I amazed with the research you made to make this particular publish amazing. Great job!

Really instructive and superb complex body part of subject material, now that’s user pleasant (:.

I would like to thank you for the efforts you have put in writing this site. I am hoping the same high-grade web site post from you in the upcoming also. Actually your creative writing skills has inspired me to get my own site now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings quickly. Your write up is a great example of it.

I was reading through some of your articles on this internet site and I believe this site is real informative! Keep putting up.

Thanx for the effort, keep up the good work Great work, I am going to start a small Blog Engine course work using your site I hope you enjoy blogging with the popular BlogEngine.net.Thethoughts you express are really awesome. Hope you will right some more posts.

We’re a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community. Your site provided us with valuable info to work on. You have done a formidable job and our whole community will be thankful to you.

Thanks – Enjoyed this post, how can I make is so that I get an email every time you write a new update?

I loved your blog.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

Major thankies for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

wow, awesome post.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Great, thanks for sharing this article post. Fantastic.

Muchos Gracias for your blog post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

Thanks for the blog article. Really Great.

Enjoyed every bit of your blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Thanks a lot for the post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Major thanks for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

I value the article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Appreciate you sharing, great post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

I think this is a real great post.Really thank you! Will read on…

Muchos Gracias for your blog.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

Thanks so much for the blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Wow, great post.Really looking forward to read more.

Thanks for the article post.Really thank you! Want more.

Thanks-a-mundo for the blog.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

I loved your post.Thanks Again. Keep writing.

Very informative blog article. Much obliged.

Hey, thanks for the article.Thanks Again.

Major thanks for the blog. Keep writing.

Very informative article.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

A big thank you for your post.Thanks Again.

Im thankful for the blog article.Much thanks again.

Im obliged for the article post. Cool.

Really informative article post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

A big thank you for your post.Really thank you! Want more.

Muchos Gracias for your article post. Much obliged.

Really informative blog article. Keep writing.

I cannot thank you enough for the article. Want more.

Looking forward to reading more. Great article.Really thank you! Cool.

Say, you got a nice article post.Much thanks again. Really Great.

Thanks again for the article post.Really thank you! Will read on…

You are really a good webmaster, you have done a well job on this topic!

Say, you got a nice blog post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

I think this is a real great blog article.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

I value the article.Really thank you!

Major thanks for the blog.Thanks Again. Awesome.

Thanks a lot for the article.Really thank you! Fantastic.

A highly requested article, we’ll teach you how to find a replica Balenciaga Handbags dealer you can actually trust.

Say, you got a nice article post.Thanks Again. Cool.

Thanks for the article.

Major thankies for the article. Awesome.

wow, awesome blog. Keep writing.

Im obliged for the blog post.Really thank you! Cool.

Thanks so much for the blog.Really thank you! Really Great.

A big thank you for your article post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Appreciate you sharing, great blog. Much obliged.

A round of applause for your article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

Im obliged for the blog.Thanks Again. Keep writing.

Im obliged for the post.Thanks Again. Really Great.

Awesome blog.Really thank you! Cool.

Very good post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Great, thanks for sharing this blog.Thanks Again. Really Cool.

Thanks a lot for the post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

I really like and appreciate your blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Thanks so much for the article post.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

Thanks-a-mundo for the blog article.Much thanks again. Awesome.

Thanks a lot for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Keep writing.

Thanks a lot for the blog article.Really thank you! Awesome.

wow, awesome blog article. Fantastic.

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Fantastic post.Thanks Again. Cool.

I loved your blog.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Im obliged for the blog post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

Appreciate you sharing, great article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

wow, awesome article post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

I really liked your article post.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

Appreciate you sharing, great blog.Much thanks again. Will read on…

Muchos Gracias for your blog post.Really thank you!

I really like and appreciate your blog article. Will read on…

I cannot thank you enough for the article post.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

Very informative post.Much thanks again. Will read on…

I really liked your post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Thanks again for the article.Thanks Again. Really Great.

I value the article.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

Really appreciate you sharing this blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Really appreciate you sharing this post.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

Major thanks for the article post.Really thank you! Cool.

Awesome blog.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

I am so grateful for your article. Really Cool.

I value the blog post. Really Great.

Thank you ever so for you article.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

Im grateful for the article.Really thank you! Will read on…

Really enjoyed this blog post.Much thanks again.

Thanks a lot for the blog article. Keep writing.

Say, you got a nice post.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Im grateful for the article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

Appreciate you sharing, great blog article. Much obliged.