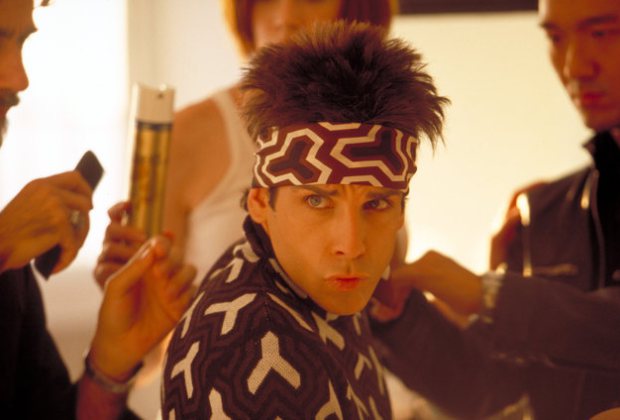

It’s amazing how often the Bechdel Test is reliant on gray areas, when the opposite is almost never the case. Within ten seconds, Zoolander joins the ranks of “comedy films that immediately pass the Reverse Bechdel Test”, with multiple men talking about a matter that has nothing to do with women.

And that’s not the only time. The movie passes the Reverse test again and again – almost every conversation is between men, about men, and only two female characters in the whole film have more than one line.

Sadly, this is typical for comedy films. Comedy is a man’s game – like most comedy films, Zoolander has exactly one main female character, filling the role of both love interest and straight man. Matilda (Christine Taylor) is the only character with half a brain, a smart and savvy journalist in a world of idiotic boy-men.

This is not to say the film is bad – it’s a comedy classic, that rare film that goes from ridiculous concept to ridiculous concept without ever wearing out its welcome. Comedically speaking, it all works – the script, the characters, the chemistry between Ben Stiller and Owen Wilson.

But it’s far from feminist.

The single conversation that qualifies for the Bechdel Test is two lines between Matilda and a female assassin. Throughout the film, the assassin has been making comments about Matilda’s “K-Mart” clothes- in the film’s climatic scene, Matilda informs her that her wardrobe is, in fact, from J.C. Penney’s.

Two lines. About clothes. It’s sad how often these films scrape by on a technicality – if two conversations were required, or a minimum of three lines of dialogue, or the exchange to go for fifteen seconds or more, this film would fail.

As it is, it passes. Just. When was the last time a film got this close to the line when the genders are flipped?

What’s more, throughout the film Jerry Stiller’s character Maury Ballstein harasses female employees. Not as part of a joke, not as part of the plot – his character is just “gropes women for no reason”. It’s never dealt with or criticized, and at the end of the film, Maury is the one who saves the day. Why is that in there? What purpose does it serve?

It doesn’t add anything to the movie, it’s just an excuse to use women as sexual props… again, not surprising for a comedy film.

(This article was originally posted on March 3rd, 2014 over at Illegitimate Theatre)

Would you be taken with exchanging hyperlinks?

There are some fascinating cut-off dates in this article however I don抰 know if I see all of them center to heart. There is some validity however I will take maintain opinion till I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like more! Added to FeedBurner as effectively

The subsequent time I read a blog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as a lot as this one. I imply, I do know it was my choice to read, but I truly thought youd have something attention-grabbing to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could possibly fix in case you werent too busy looking for attention.

After examine just a few of the blog posts on your web site now, and I actually like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site list and shall be checking again soon. Pls try my web site as well and let me know what you think.

This web page is mostly a stroll-by for all of the information you wished about this and didn抰 know who to ask. Glimpse right here, and you抣l positively discover it.

That is the precise weblog for anyone who desires to find out about this topic. You realize a lot its nearly exhausting to argue with you (not that I really would need匟aHa). You undoubtedly put a brand new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just nice!

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..extra wait .. ?

I precisely wished to thank you very much once again. I’m not certain what I would have handled in the absence of those secrets shown by you regarding such topic. Previously it was a very intimidating circumstance for me, nevertheless taking a look at the very specialized avenue you treated the issue made me to jump for gladness. Now i am happier for your work and then wish you comprehend what an amazing job you have been providing teaching men and women through your websites. More than likely you have never encountered any of us.

Your home is valueble for me. Thanks!?

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!?

I am typically to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your website and maintain checking for new information.

You must take part in a contest for among the best blogs on the web. I’ll suggest this web site!

There’s noticeably a bundle to find out about this. I assume you made certain good points in features also.

An attention-grabbing discussion is value comment. I feel that you must write more on this topic, it might not be a taboo topic but generally persons are not sufficient to talk on such topics. To the next. Cheers

An attention-grabbing discussion is price comment. I believe that you should write more on this matter, it won’t be a taboo subject however typically people are not sufficient to speak on such topics. To the next. Cheers

I used to be more than happy to search out this net-site.I needed to thanks for your time for this glorious learn!! I definitely having fun with each little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you weblog post.

You made some respectable factors there. I regarded on the internet for the difficulty and found most people will associate with together with your website.

Thank you a lot for providing individuals with a very nice possiblity to read in detail from this website. It is always so excellent and full of a lot of fun for me and my office fellow workers to visit your website particularly 3 times every week to read the newest stuff you have got. And indeed, I am just always pleased with all the wonderful opinions served by you. Some 2 ideas on this page are unequivocally the very best we’ve ever had.

There are some fascinating time limits on this article but I don抰 know if I see all of them middle to heart. There may be some validity but I’ll take maintain opinion till I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like more! Added to FeedBurner as properly

You made some decent points there. I appeared on the web for the issue and found most individuals will go together with along with your website.

This is the appropriate weblog for anybody who needs to find out about this topic. You realize a lot its almost laborious to argue with you (not that I really would need匟aHa). You undoubtedly put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, simply nice!

very nice put up, i certainly love this web site, carry on it

Would you be excited by exchanging hyperlinks?

Aw, this was a really nice post. In concept I want to put in writing like this moreover ?taking time and actual effort to make a very good article?however what can I say?I procrastinate alot and on no account appear to get something done.

I’m usually to running a blog and i actually admire your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your website and preserve checking for new information.

Nice post. I learn something tougher on different blogs everyday. It’ll at all times be stimulating to read content from other writers and observe a bit of one thing from their store. I抎 desire to use some with the content on my blog whether you don抰 mind. Natually I抣l offer you a link on your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read something like this before. So good to find somebody with some authentic ideas on this subject. realy thank you for beginning this up. this web site is something that’s needed on the internet, somebody with a bit originality. useful job for bringing something new to the web!

Would you be keen on exchanging hyperlinks?

I simply needed to thank you very much once more. I do not know the things I might have made to happen without those pointers shown by you over my question. This has been a challenging condition for me personally, but spending time with a specialised tactic you handled the issue made me to leap for gladness. I am just thankful for this guidance and then pray you know what a powerful job you have been providing instructing many people through the use of a site. I am certain you’ve never got to know any of us.

I抎 need to verify with you here. Which is not something I usually do! I take pleasure in reading a submit that can make folks think. Additionally, thanks for permitting me to remark!

After I initially commented I clicked the -Notify me when new feedback are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get 4 emails with the identical comment. Is there any method you possibly can remove me from that service? Thanks!

Hi there! I simply wish to give a huge thumbs up for the good info you’ve gotten here on this post. I will probably be coming again to your blog for more soon.

I抎 need to check with you here. Which isn’t one thing I often do! I enjoy studying a post that may make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to comment!

After I initially commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get 4 emails with the same comment. Is there any way you may take away me from that service? Thanks!

There is noticeably a bundle to learn about this. I assume you made certain good factors in features also.

My wife and i got quite contented Peter could conclude his analysis via the ideas he had through the weblog. It is now and again perplexing just to happen to be giving freely solutions that people today might have been selling. And we see we’ve got the writer to be grateful to for this. The main explanations you made, the easy blog navigation, the friendships you can make it possible to promote – it is all amazing, and it’s really assisting our son in addition to us do think this issue is satisfying, and that is particularly pressing. Many thanks for the whole lot!

You must participate in a contest for the most effective blogs on the web. I’ll advocate this website!

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!?

Would you be occupied with exchanging links?

You need to take part in a contest for probably the greatest blogs on the web. I’ll advocate this website!

There are definitely loads of details like that to take into consideration. That may be a great point to bring up. I provide the thoughts above as general inspiration but clearly there are questions just like the one you convey up where crucial thing will be working in sincere good faith. I don?t know if greatest practices have emerged around issues like that, but I am sure that your job is clearly recognized as a good game. Both girls and boys feel the impact of just a second抯 pleasure, for the remainder of their lives.

After research a couple of of the weblog posts on your website now, and I actually like your method of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site checklist and might be checking back soon. Pls check out my web page as effectively and let me know what you think.

I discovered your blog site on google and examine a couple of of your early posts. Proceed to keep up the superb operate. I just extra up your RSS feed to my MSN News Reader. In search of forward to studying extra from you later on!?

My spouse and i ended up being absolutely cheerful Louis managed to finish up his reports through your precious recommendations he gained out of your web page. It is now and again perplexing to just choose to be giving out solutions that many the rest could have been trying to sell. We consider we have got the website owner to appreciate for that. The entire illustrations you’ve made, the easy blog menu, the relationships you give support to foster – it’s got many amazing, and it’s facilitating our son and our family imagine that this situation is interesting, which is wonderfully pressing. Thanks for all the pieces!

you’ve an amazing weblog here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

After examine a couple of of the weblog posts in your website now, and I really like your manner of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site listing and shall be checking back soon. Pls take a look at my web page as effectively and let me know what you think.

This actually answered my drawback, thanks!

This is the suitable weblog for anybody who desires to find out about this topic. You realize a lot its virtually exhausting to argue with you (not that I really would need匟aHa). You positively put a new spin on a subject thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, just nice!

There are certainly plenty of particulars like that to take into consideration. That could be a nice point to bring up. I offer the thoughts above as basic inspiration but clearly there are questions like the one you carry up the place an important factor will likely be working in sincere good faith. I don?t know if finest practices have emerged around issues like that, but I am sure that your job is clearly identified as a good game. Both boys and girls really feel the impression of only a moment抯 pleasure, for the rest of their lives.

After I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a remark is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any method you possibly can take away me from that service? Thanks!

An fascinating discussion is worth comment. I think that it is best to write more on this subject, it won’t be a taboo subject however usually individuals are not sufficient to talk on such topics. To the next. Cheers

The next time I learn a blog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as a lot as this one. I imply, I do know it was my option to read, however I really thought youd have something attention-grabbing to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about one thing that you might fix in case you werent too busy on the lookout for attention.

You made some respectable factors there. I appeared on the web for the difficulty and found most people will associate with together with your website.

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..extra wait .. ?

Spot on with this write-up, I actually suppose this web site wants far more consideration. I抣l most likely be once more to read much more, thanks for that info.

This actually answered my problem, thank you!

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!?

I was suggested this website by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my problem. You’re wonderful! Thanks!

Nice post. I study something more challenging on completely different blogs everyday. It’ll at all times be stimulating to learn content from other writers and practice somewhat one thing from their store. I?d desire to use some with the content material on my blog whether you don?t mind. Natually I?ll give you a hyperlink on your net blog. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for this glorious article. Yet another thing to mention is that nearly all digital cameras are available equipped with a zoom lens that permits more or less of your scene to be included by way of ‘zooming’ in and out. Most of these changes in {focus|focusing|concentration|target|the a**** length are reflected from the viewfinder and on big display screen at the back of the actual camera.

http://www.spotnewstrend.com is a trusted latest USA News and global news provider. Spotnewstrend.com website provides latest insights to new trends and worldwide events. So keep visiting our website for USA News, World News, Financial News, Business News, Entertainment News, Celebrity News, Sport News, NBA News, NFL News, Health News, Nature News, Technology News, Travel News.

Hello, you used to write excellent, but the last several posts have been kinda boring… I miss your great writings. Past several posts are just a bit out of track! come on!

Hey very cool site!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your site and take the feeds also?I am happy to find numerous useful info here in the post, we need work out more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

I have noticed that online diploma is getting preferred because accomplishing your college degree online has turned into a popular solution for many people. A large number of people have not really had a chance to attend a normal college or university yet seek the increased earning potential and a better job that a Bachelors Degree grants. Still some others might have a college degree in one field but want to pursue a thing they now develop an interest in.

I’ve been browsing online greater than 3 hours nowadays, but I never discovered any fascinating article like yours. It is pretty value enough for me. In my opinion, if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the web will probably be much more useful than ever before.

Hi, Neat post. There is a problem with your site in internet explorer, would check this? IE still is the market leader and a big portion of people will miss your great writing because of this problem.

What an informative and well-researched article! The author’s meticulousness and capability to present complex ideas in a digestible manner is truly admirable. I’m extremely captivated by the breadth of knowledge showcased in this piece. Thank you, author, for offering your expertise with us. This article has been a game-changer!

http://www.bestartdeals.com.au is Australia’s Trusted Online Canvas Prints Art Gallery. We offer 100 percent high quality budget wall art prints online since 2009. Get 30-70 percent OFF store wide sale, Prints starts $20, FREE Delivery Australia, NZ, USA. We do Worldwide Shipping across 50+ Countries.

I discovered your blog website on google and verify a couple of of your early posts. Proceed to maintain up the very good operate. I just extra up your RSS feed to my MSN Information Reader. In search of ahead to reading more from you in a while!?

Hello! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with SEO? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good results. If you know of any please share. Thank you!

I have observed that of all sorts of insurance, health insurance is the most debatable because of the discord between the insurance cover company’s obligation to remain making money and the buyer’s need to have insurance coverage. Insurance companies’ commission rates on health and fitness plans are extremely low, so some companies struggle to make a profit. Thanks for the ideas you reveal through this blog.

Great post here. One thing I would like to say is that often most professional domains consider the Bachelor Degree just as the entry level requirement for an online certification. Though Associate Certifications are a great way to begin, completing ones Bachelors presents you with many doorways to various professions, there are numerous online Bachelor Course Programs available via institutions like The University of Phoenix, Intercontinental University Online and Kaplan. Another issue is that many brick and mortar institutions provide Online editions of their certifications but typically for a significantly higher charge than the institutions that specialize in online college degree programs.

Nice post. I used to be checking constantly this blog and I am impressed! Very useful information specifically the ultimate section 🙂 I take care of such info much. I was seeking this particular information for a long time. Thanks and good luck.

I like the helpful information you provide in your articles. I?ll bookmark your blog and check again here regularly. I’m quite sure I will learn lots of new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!

Thanks for the concepts you write about through your blog. In addition, many young women which become pregnant do not even seek to get medical insurance because they are full of fearfulness they would not qualify. Although a few states today require that insurers supply coverage no matter what about the pre-existing conditions. Rates on these guaranteed plans are usually higher, but when with the high cost of health care bills it may be any safer approach to take to protect a person’s financial future.

Together with everything which seems to be developing within this particular area, a significant percentage of opinions happen to be quite refreshing. Having said that, I appologize, but I can not subscribe to your whole theory, all be it stimulating none the less. It seems to me that your opinions are generally not totally validated and in simple fact you are generally your self not really entirely confident of your argument. In any case I did take pleasure in reading through it.

I will immediately take hold of your rss feed as I can not to find your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Please permit me recognise so that I may just subscribe. Thanks.

Hey There. I found your blog using msn. This is a very well written article. I will be sure to bookmark it and come back to read more of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I will definitely comeback.

Today, I went to the beach with my kids. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She put the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is completely off topic but I had to tell someone!

Many thanks for this article. I’d also like to express that it can become hard when you find yourself in school and merely starting out to create a long credit ranking. There are many college students who are merely trying to make it and have long or positive credit history can occasionally be a difficult thing to have.

Thanks for the ideas shared using your blog. Something else I would like to mention is that losing weight is not information about going on a dietary fad and trying to shed as much weight as possible in a couple of days. The most effective way to shed pounds is by using it little by little and using some basic tips which can assist you to make the most through your attempt to slim down. You may realize and already be following some tips, although reinforcing information never does any damage.

Wow, awesome weblog structure! How lengthy have you ever been blogging for? you made running a blog look easy. The whole glance of your web site is magnificent, as neatly as the content material!

This article is a breath of fresh air! The author’s unique perspective and insightful analysis have made this a truly fascinating read. I’m appreciative for the effort he has put into crafting such an informative and thought-provoking piece. Thank you, author, for offering your knowledge and igniting meaningful discussions through your exceptional writing!

Hi! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new iphone 3gs! Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the fantastic work!

Yesterday, while I was at work, my cousin stole my iphone and tested to see if it can survive a forty foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is totally off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Hi there, You have performed an incredible job. I will definitely digg it and individually recommend to my friends. I’m confident they’ll be benefited from this site.

Thanks , I’ve just been looking for information about this subject for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far. But, what about the conclusion? Are you sure about the source?

Thanks for your submission. Another thing is that just being a photographer will involve not only issues in taking award-winning photographs but also hardships in establishing the best digital camera suited to your needs and most especially struggles in maintaining the caliber of your camera. This is very accurate and noticeable for those photographers that are in capturing the actual nature’s exciting scenes – the mountains, the forests, the actual wild or even the seas. Going to these amazing places definitely requires a dslr camera that can surpass the wild’s harsh conditions.

With havin so much written content do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright violation? My website has a lot of unique content I’ve either written myself or outsourced but it appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my permission. Do you know any techniques to help prevent content from being stolen? I’d really appreciate it.

excellent post, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector don’t notice this. You must continue your writing. I’m sure, you’ve a great readers’ base already!

Out of my research, shopping for electronic devices online can for sure be expensive, nevertheless there are some tips and tricks that you can use to acquire the best bargains. There are continually ways to discover discount offers that could help to make one to come across the best consumer electronics products at the cheapest prices. Interesting blog post.

I learned more new stuff on this weight-loss issue. One particular issue is a good nutrition is especially vital whenever dieting. A big reduction in junk food, sugary food, fried foods, sugary foods, pork, and white flour products could possibly be necessary. Holding wastes parasites, and poisons may prevent targets for fat loss. While specific drugs temporarily solve the problem, the unpleasant side effects aren’t worth it, and so they never present more than a temporary solution. It’s a known indisputable fact that 95 of dietary fads fail. Many thanks sharing your ideas on this blog site.

There are some fascinating cut-off dates on this article however I don?t know if I see all of them center to heart. There’s some validity but I will take hold opinion until I look into it further. Good article , thanks and we would like extra! Added to FeedBurner as effectively

Hello would you mind letting me know which web host you’re working with? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 completely different web browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you suggest a good web hosting provider at a honest price? Kudos, I appreciate it!

Hello there, I found your site by way of Google at the same time as looking for a related matter, your website came up, it appears to be like great. I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Hey! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any trouble with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing several weeks of hard work due to no data backup. Do you have any methods to protect against hackers?

You really make it seem so easy together with your presentation however I find this topic to be actually something that I think I might never understand. It seems too complicated and very vast for me. I’m looking ahead for your next put up, I will attempt to get the cling of it!

I would also like to express that most individuals that find themselves with no health insurance are generally students, self-employed and people who are unemployed. More than half of the uninsured are really under the age of Thirty-five. They do not feel they are looking for health insurance since they are young and healthy. Their own income is usually spent on property, food, along with entertainment. A lot of people that do represent the working class either whole or as a hobby are not given insurance by their jobs so they head out without due to rising price of health insurance in the us. Thanks for the suggestions you share through this website.

After looking into a few of the blog posts on your site, I honestly appreciate your way of writing a blog. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back in the near future. Please visit my website too and tell me your opinion.

I have noticed that clever real estate agents almost everywhere are Promotion. They are acknowledging that it’s in addition to placing a sign in the front place. It’s really in relation to building human relationships with these retailers who sooner or later will become buyers. So, while you give your time and efforts to supporting these sellers go it alone : the “Law regarding Reciprocity” kicks in. Great blog post.

One important issue is that if you find yourself searching for a education loan you may find that you’ll want a co-signer. There are many scenarios where this is true because you could find that you do not employ a past credit rating so the bank will require you have someone cosign the financing for you. Good post.

Hmm is anyone else having problems with the pictures on this blog loading? I’m trying to determine if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any suggestions would be greatly appreciated.

Great post. I used to be checking continuously this blog and I’m impressed! Very helpful information specially the remaining part 🙂 I handle such information a lot. I was looking for this particular information for a long time. Thank you and best of luck.

I got what you intend, thankyou for putting up.Woh I am thankful to find this website through google.

🌌 Wow, blog ini seperti perjalanan kosmik melayang ke alam semesta dari keajaiban! 💫 Konten yang menegangkan di sini adalah perjalanan rollercoaster yang mendebarkan bagi imajinasi, memicu kegembiraan setiap saat. 🎢 Baik itu inspirasi, blog ini adalah sumber wawasan yang inspiratif! #KemungkinanTanpaBatas Berangkat ke dalam perjalanan kosmik ini dari penemuan dan biarkan pemikiran Anda terbang! 🌈 Jangan hanya mengeksplorasi, alami kegembiraan ini! #BahanBakarPikiran 🚀 akan bersyukur untuk perjalanan menyenangkan ini melalui alam keajaiban yang menakjubkan! 🌍

💫 Wow, blog ini seperti roket melayang ke galaksi dari kemungkinan tak terbatas! 🎢 Konten yang menarik di sini adalah perjalanan rollercoaster yang mendebarkan bagi pikiran, memicu kegembiraan setiap saat. 🎢 Baik itu gayahidup, blog ini adalah sumber wawasan yang menarik! #PetualanganMenanti 🚀 ke dalam petualangan mendebarkan ini dari imajinasi dan biarkan pikiran Anda berkelana! 🌈 Jangan hanya membaca, rasakan sensasi ini! #BahanBakarPikiran Pikiran Anda akan bersyukur untuk perjalanan mendebarkan ini melalui ranah keajaiban yang menakjubkan! 🚀

I have noticed that of all types of insurance, health insurance coverage is the most questionable because of the clash between the insurance policy company’s duty to remain profitable and the consumer’s need to have insurance coverage. Insurance companies’ revenue on wellness plans are certainly low, thus some firms struggle to generate income. Thanks for the ideas you share through this web site.

A few things i have often told persons is that while looking for a good on the net electronics retail store, there are a few issues that you have to consider. First and foremost, you need to make sure to locate a reputable along with reliable shop that has enjoyed great testimonials and rankings from other people and business world experts. This will ensure that you are getting through with a well-known store providing you with good services and assistance to their patrons. Thank you for sharing your notions on this site.

Thank you for your article. Much obliged.

I used to be very pleased to search out this net-site.I wished to thanks in your time for this excellent learn!! I undoubtedly enjoying every little bit of it and I’ve you bookmarked to take a look at new stuff you blog post.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It actually was a entertainment account it. Look complex to far delivered agreeable from you! However, how could we keep up a correspondence?

I am so grateful for your post.Thanks Again. Want more.

you’re in point of fact a good webmaster. The website loading velocity is amazing. It seems that you’re doing any unique trick. In addition, The contents are masterpiece. you’ve done a fantastic job on this topic!

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read something like this before. So good to seek out any person with some original ideas on this subject. realy thanks for starting this up. this web site is one thing that’s needed on the net, someone with somewhat originality. helpful job for bringing something new to the internet!

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you really understand what you’re speaking about! Bookmarked. Please additionally discuss with my website =). We could have a hyperlink exchange contract between us!

Nice post. I was checking constantly this weblog and I am impressed! Extremely helpful information specially the remaining phase 🙂 I take care of such info much. I used to be seeking this particular information for a very long time. Thanks and good luck.

I was recommended this website by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my difficulty. You’re amazing! Thanks!

I’ve learned a few important things as a result of your post. I might also like to mention that there is a situation that you will have a loan and never need a cosigner such as a Federal government Student Support Loan. But when you are getting a loan through a classic bank then you need to be able to have a cosigner ready to help you. The lenders can base their decision using a few aspects but the most important will be your credit rating. There are some financial institutions that will furthermore look at your job history and choose based on that but in almost all cases it will depend on your credit score.

Hello there, I discovered your site by way of Google whilst looking for a related subject, your website came up, it seems to be good. I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Furthermore, i believe that mesothelioma is a uncommon form of cancers that is often found in all those previously subjected to asbestos. Cancerous cellular material form from the mesothelium, which is a safety lining which covers many of the body’s areas. These cells normally form within the lining with the lungs, abdominal area, or the sac which encircles one’s heart. Thanks for revealing your ideas.

Nice read, I just passed this onto a friend who was doing some research on that. And he actually bought me lunch as I found it for him smile Therefore let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch!

Helpful info. Lucky me I found your website by accident, and I’m stunned why this coincidence didn’t came about in advance! I bookmarked it.

Thanks for your article on this blog. From my experience, occasionally softening way up a photograph could provide the photography with a little bit of an artsy flare. Often times however, the soft cloud isn’t just what you had in your mind and can in many cases spoil an otherwise good image, especially if you intend on enlarging this.

What?s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It positively useful and it has aided me out loads. I’m hoping to give a contribution & assist other customers like its aided me. Great job.

One other thing to point out is that an online business administration study course is designed for scholars to be able to smoothly proceed to bachelors degree education. The Ninety credit college degree meets the other bachelor college degree requirements then when you earn your current associate of arts in BA online, you’ll have access to the modern technologies in this particular field. Some reasons why students want to get their associate degree in business is because they can be interested in this area and want to receive the general education and learning necessary before jumping right into a bachelor college diploma program. Thanks alot : ) for the tips you provide inside your blog.

Can I just say what a reduction to search out somebody who truly knows what theyre speaking about on the internet. You positively know learn how to deliver a difficulty to light and make it important. Extra people must read this and perceive this facet of the story. I cant imagine youre no more popular since you undoubtedly have the gift.

Holy moly, this blog is an unbelievable goldmine of knowledge! 😍💎 I could not stop reading from start to finish. 📚💫 Every word is like a wonderful charm that keeps me enchanted. Can’t eagerly anticipate for additional mind-boggling posts! 🚀🔥 #FantasticSite #IncredibleContent 🌟👏

I’m not sure exactly why but this site is loading extremely slow for me. Is anyone else having this issue or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

Excellent post. I used to be checking constantly this weblog and I am impressed! Extremely helpful info specifically the remaining phase 🙂 I care for such info much. I was looking for this particular information for a very lengthy time. Thanks and best of luck.

Получение Ð¾Ð±Ñ€Ð°Ð·Ð¾Ð²Ð°Ð½Ð¸Ñ Ð¾Ð±Ñзательно Ð´Ð»Ñ Ñ‚Ñ€ÑƒÐ´Ð¾ÑƒÑтройÑтва на позицию. Иногда ÑлучаютÑÑ Ñитуации, когда ранее полученное ÑвидетельÑтво неприменим Ð´Ð»Ñ Ð²Ñ‹Ð±Ñ€Ð°Ð½Ð½Ð¾Ð¹ трудовой Ñферы. Покупка образовательного документа в МоÑкве разрешит Ñтот Ð²Ð¾Ð¿Ñ€Ð¾Ñ Ð¸ обеÑпечит процветание в будущем – https://kupit-diplom1.com/. СущеÑтвует множеÑтво факторов, побуждающих приобретение документа об образовании в МоÑкве. ПоÑле неÑкольких лет работы повдруг может потребоватьÑÑ ÑƒÐ½Ð¸Ð²ÐµÑ€ÑитетÑкий диплом. Работодатель вправе менÑÑ‚ÑŒ Ñ‚Ñ€ÐµÐ±Ð¾Ð²Ð°Ð½Ð¸Ñ Ðº перÑоналу и поÑтавить Ð²Ð°Ñ Ð¿ÐµÑ€ÐµÐ´ выбором – получить диплом или покинуть должноÑÑ‚ÑŒ. Учеба на дневном отделении вызывает затраты времени и уÑилий, а диÑтанционное обучение — требует денег на Ñкзамены. Ð’ подобных обÑтоÑтельÑтвах более выгодно купить готовый документ. ЕÑли вы ознакомлены Ñ Ð¾ÑобенноÑÑ‚Ñми Ñвоей будущей Ñпециализации и научилиÑÑŒ необходимым навыкам, не имеет ÑмыÑла тратить годы на обучение в ВУЗе. ПлюÑÑ‹ заказа аттеÑтата включают быÑтрую изготовку, идеальное ÑходÑтво Ñ Ð¾Ñ€Ð¸Ð³Ð¸Ð½Ð°Ð»Ð¾Ð¼, доÑтупные цены, гарантированное трудоуÑтройÑтво, ÑамоÑтоÑтельный выбор оценок и комфортную доÑтавку. Ðаша фирма предлагает возможноÑÑ‚ÑŒ вÑем желающим получить желаемую ÑпециальноÑÑ‚ÑŒ. Цена Ð¸Ð·Ð³Ð¾Ñ‚Ð¾Ð²Ð»ÐµÐ½Ð¸Ñ Ð°Ñ‚Ñ‚ÐµÑтатов приемлема, что делает Ñту покупку доÑтупной Ð´Ð»Ñ Ð²Ñех.

Thank you a lot for sharing this with all folks you really recognize what you are speaking about! Bookmarked. Kindly additionally discuss with my website =). We may have a hyperlink exchange agreement between us!

I believe that avoiding ready-made foods may be the first step in order to lose weight. They may taste fine, but processed foods have got very little nutritional value, making you take in more to have enough energy to get over the day. In case you are constantly feeding on these foods, transitioning to grain and other complex carbohydrates will assist you to have more electricity while consuming less. Good blog post.

My brother recommended I might like this website. He was entirely right. This post truly made my day. You cann’t imagine just how much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!

Hey there! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any tips?

I do believe that a foreclosures can have a important effect on the client’s life. Property foreclosures can have a 6 to several years negative effect on a borrower’s credit report. Any borrower who has applied for a home loan or any loans even, knows that a worse credit rating is actually, the more tough it is for any decent mortgage. In addition, it might affect the borrower’s chance to find a really good place to lease or rent, if that gets to be the alternative homes solution. Thanks for your blog post.

magnificent points altogether, you simply received a brand new reader. What would you recommend in regards to your put up that you made some days ago? Any positive?

Nearly all of whatever you articulate is supprisingly precise and that makes me wonder why I had not looked at this with this light previously. Your piece really did switch the light on for me as far as this particular issue goes. But there is actually just one point I am not necessarily too cozy with and whilst I make an effort to reconcile that with the actual main theme of your point, allow me see exactly what all the rest of the subscribers have to point out.Well done.

Приобрести свидетельство в Москве – выгодное предложение для тех, кто проживает в Москве.

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an extremely long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t show up. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyway, just wanted to say fantastic blog!

I think this is among the most significant information for me. And i’m glad reading your article. But should remark on few general things, The site style is great, the articles is really nice : D. Good job, cheers

You made some respectable points there. I looked on the internet for the difficulty and found most individuals will go along with with your website.

В текущих ситуациях сложно сделать будущее обеспеченных без высшего образования – https://www.diplomex.com/. Без академического образования получить работу на должность с приличной оплатой труда и удобными условиями практически невозможно. Достаточно много индивидуумов, получивших информацию о подходящей вакансии, приходится от нее отклониться, не имея такого документа. Однако проблему можно разрешить, если заказать диплом о высшем образовании, расценка которого будет подъемная в сравнивание со стоимостью обучения. Особенности покупки диплома о высшем уровне образовании Если человеку требуется всего лишь демонстрировать документ близким, из-за причины, что они не удалось закончить учебу по любой причинам, можно заказать недорогую топографическую копию. Однако, если его придется показывать при нахождении работы, к теме стоит подойти более серьезно.

Hi there! This is my 1st comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I genuinely enjoy reading through your posts. Can you suggest any other blogs/websites/forums that deal with the same topics? Appreciate it!

hello there and thank you for your info ? I have definitely picked up something new from right here. I did however expertise several technical points using this website, as I experienced to reload the website a lot of times previous to I could get it to load correctly. I had been wondering if your hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but slow loading instances times will very frequently affect your placement in google and can damage your quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Well I am adding this RSS to my e-mail and could look out for much more of your respective interesting content. Ensure that you update this again soon..

You actually make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this matter to be really something that I think I would never understand. It seems too complicated and extremely broad for me. I’m looking forward for your next post, I?ll try to get the hang of it!

This will be a fantastic website, would you be involved in doing an interview regarding how you developed it? If so e-mail me!

Excellent goods from you, man. I’ve have in mind your stuff previous to and you’re just too fantastic. I really like what you’ve got here, really like what you are saying and the way in which in which you assert it. You make it entertaining and you still take care of to stay it smart. I can’t wait to read much more from you. This is actually a terrific website.

hello!,I like your writing very much! share we communicate more about your article on AOL? I require an expert on this area to solve my problem. May be that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

I’m in awe of the author’s capability to make complicated concepts approachable to readers of all backgrounds. This article is a testament to his expertise and passion to providing helpful insights. Thank you, author, for creating such an captivating and insightful piece. It has been an absolute pleasure to read!

Thanks for the recommendations shared on your own blog. One more thing I would like to mention is that weight reduction is not information on going on a dietary fads and trying to get rid of as much weight as you can in a set period of time. The most effective way to burn fat is by getting it bit by bit and right after some basic ideas which can provide help to make the most from your attempt to lose fat. You may understand and already be following many of these tips, although reinforcing expertise never damages.

Whats up this is somewhat of off topic but I was wanting to know if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding know-how so I wanted to get advice from someone with experience. Any help would be greatly appreciated!

whoah this blog is excellent i love reading your posts. Keep up the great work! You know, lots of people are looking around for this information, you could aid them greatly.

My developer is trying to convince me to move to .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the expenses. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using Movable-type on a number of websites for about a year and am anxious about switching to another platform. I have heard great things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can transfer all my wordpress posts into it? Any kind of help would be greatly appreciated!

Hey there! I know this is kinda off topic but I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in exchanging links or maybe guest authoring a blog post or vice-versa? My site covers a lot of the same subjects as yours and I think we could greatly benefit from each other. If you might be interested feel free to shoot me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Wonderful blog by the way!

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having trouble locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an e-mail. I’ve got some creative ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it develop over time.

Hi there, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam feedback? If so how do you stop it, any plugin or anything you can advise? I get so much lately it’s driving me crazy so any assistance is very much appreciated.

After study a couple of of the weblog posts on your web site now, and I truly like your means of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site checklist and can be checking back soon. Pls take a look at my site as well and let me know what you think.

I have come across that currently, more and more people are attracted to surveillance cameras and the discipline of digital photography. However, to be a photographer, you must first expend so much time frame deciding the model of video camera to buy as well as moving store to store just so you might buy the least expensive camera of the brand you have decided to pick out. But it isn’t going to end now there. You also have to take into account whether you should obtain a digital dslr camera extended warranty. Thanks a bunch for the good guidelines I gained from your blog.

Thank you for another fantastic article. Where else could anyone get that kind of information in such an ideal way of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I’m on the look for such information.

feed

Hi, i think that i noticed you visited my weblog thus i got here to ?return the desire?.I’m trying to in finding issues to improve my site!I guess its ok to use some of your concepts!!

you’re really a good webmaster. The web site loading speed is incredible. It seems that you’re doing any unique trick. Moreover, The contents are masterwork. you’ve done a fantastic job on this topic!

I have mastered some important matters through your website post. One other stuff I would like to say is that there are several games in the marketplace designed especially for preschool age children. They incorporate pattern identification, colors, creatures, and models. These typically focus on familiarization as an alternative to memorization. This keeps little ones engaged without sensing like they are learning. Thanks

My brother recommended I might like this blog. He was totally right. This post truly made my day. You can not imagine simply how much time I had spent for this information! Thanks!

The information shared is of top quality which has to get appreciated at all levels. Well done…

depannage-volet-roulant-nice.fr

Thanks for your blog post. What I would like to add is that laptop or computer memory is required to be purchased when your computer is unable to cope with that which you do along with it. One can install two RAM boards having 1GB each, for example, but not one of 1GB and one having 2GB. One should check the maker’s documentation for the PC to make certain what type of memory is required.

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read anything like this before. So good to find anyone with some original ideas on this subject. realy thanks for beginning this up. this web site is one thing that is wanted on the internet, someone with a bit of originality. helpful job for bringing something new to the internet!

Купить диплом о среднем образовании – это вариант скоро достать бумагу об академическом статусе на бакалавр уровне безо излишних хлопот и расходов времени. В Москве имеются различные опций подлинных свидетельств бакалавров, обеспечивающих комфорт и удобство в процессе..

A great post without any doubt.

Nice i really enjoyed reading your blogs. Keep on posting. Thanks

Whats up very cool web site!! Man .. Excellent .. Wonderful .. I will bookmark your website and take the feeds additionally?I am satisfied to find numerous useful information right here in the publish, we need develop more techniques in this regard, thank you for sharing. . . . . .

I have been reading out some of your articles and i can claim pretty good stuff. I will definitely bookmark your blog.

An attention-grabbing discussion is worth comment. I believe that it’s best to write more on this matter, it won’t be a taboo subject but usually persons are not sufficient to talk on such topics. To the next. Cheers

The information shared is of top quality which has to get appreciated at all levels. Well done…

Внутри Москве заказать аттестат – это практичный и экспресс способ достать нужный бумага без дополнительных трудностей. Большое количество фирм предлагают услуги по созданию и торговле дипломов различных образовательных учреждений – https://russa-diploms-srednee.com/. Ассортимент дипломов в Москве огромен, включая бумаги о высшем уровне и среднем образовании, аттестаты, свидетельства вузов и вузов. Главное плюс – способность достать диплом подлинный документ, подтверждающий подлинность и высокое стандарт. Это гарантирует уникальная защита против фальсификаций и предоставляет возможность использовать диплом для разнообразных целей. Таким образом, заказ диплома в столице России становится надежным и оптимальным выбором для данных, кто хочет достичь успеха в карьере.

Good website! I really love how it is simple on my eyes and the data are well written. I am wondering how I might be notified whenever a new post has been made. I’ve subscribed to your RSS which must do the trick! Have a great day!

My developer is trying to convince me to move to .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the costs. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using WordPress on numerous websites for about a year and am nervous about switching to another platform. I have heard very good things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can import all my wordpress content into it? Any help would be really appreciated!

Hello my friend! I wish to say that this post is amazing, nice written and include almost all important infos. I?d like to look more posts like this .

Something more important is that when you are evaluating a good on the web electronics retail outlet, look for web shops that are constantly updated, retaining up-to-date with the hottest products, the very best deals, along with helpful information on services. This will ensure you are doing business with a shop that stays ahead of the competition and give you what you ought to make knowledgeable, well-informed electronics buying. Thanks for the vital tips I’ve learned from the blog.

Hello! Someone in my Myspace group shared this site with us so I came to look it over. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Exceptional blog and excellent design.

Its such as you read my mind! You seem to understand a lot about this, such as you wrote the e book in it or something. I feel that you just can do with some p.c. to power the message home a little bit, but instead of that, that is fantastic blog. A fantastic read. I will certainly be back.

Holy cow! I’m in awe of the author’s writing skills and capability to convey complex concepts in a concise and clear manner. This article is a real treasure that deserves all the praise it can get. Thank you so much, author, for offering your expertise and providing us with such a valuable resource. I’m truly appreciative!

Do you have a spam issue on this website; I also am a blogger, and I was curious about your situation; many of us have created some nice practices and we are looking to swap methods with other folks, please shoot me an email if interested.

A great post without any doubt.

Great website. Plenty of useful info here. I?m sending it to several friends ans also sharing in delicious. And of course, thanks in your sweat!

Thank you for sharing indeed great looking !

Howdy! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new iphone 4! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the superb work!

You’ve articulated your points with such finesse. Truly a pleasure to enjoy reading.

I appreciate the balance and fairness in your writing. Great job!

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my site so i came to ?return the favor?.I am attempting to find things to improve my website!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

One thing I want to say is the fact that before buying more personal computer memory, have a look at the machine in which it would be installed. Should the machine is running Windows XP, for instance, a memory ceiling is 3.25GB. Putting in more than this would purely constitute a waste. Be sure that one’s mother board can handle the actual upgrade quantity, as well. Great blog post.

It?s actually a great and useful piece of info. I am glad that you just shared this helpful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

Hello there, You have done an incredible job. I?ll definitely digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I am sure they will be benefited from this website.

you have got an ideal weblog right here! would you wish to make some invite posts on my blog?

Wonderful postings Cheers!

I’m bookmarking this for future reference. Your advice is spot on!

Your home is valueble for me. Thanks!?

Thank you for adding value to the conversation with your insights.

This article was a delightful enjoy reading. Your passion is clearly visible!

This article was a delightful enjoy reading. Your passion is clearly visible!

Thanks for making me to get new concepts about computer systems. I also hold the belief that certain of the best ways to maintain your notebook in perfect condition is with a hard plastic material case, or maybe shell, that fits over the top of the computer. A lot of these protective gear are model targeted since they are made to fit perfectly on the natural casing. You can buy these directly from the owner, or from third party places if they are available for your mobile computer, however only a few laptop will have a cover on the market. Just as before, thanks for your tips.

Thank you sharing these wonderful articles. In addition, the optimal travel and medical insurance program can often relieve those fears that come with travelling abroad. A medical crisis can before long become very costly and that’s certain to quickly set a financial stress on the family’s finances. Setting up in place the perfect travel insurance program prior to setting off is well worth the time and effort. Cheers

I have noticed that credit repair activity must be conducted with techniques. If not, you might find yourself causing harm to your position. In order to realize your aspirations in fixing your credit rating you have to take care that from this minute you pay any monthly costs promptly before their slated date. It really is significant for the reason that by not accomplishing so, all other steps that you will decide on to improve your credit rating will not be successful. Thanks for giving your thoughts.

You’ve presented a complex topic in a clear and engaging way. Bravo!

Nice i really enjoyed reading your blogs. Keep on posting. Thanks

You have a unique perspective that I find incredibly valuable. Thank you for sharing.

Superb blog you have here but I was curious about if you knew of any community forums that cover the same topics discussed here? I’d really like to be a part of community where I can get comments from other experienced people that share the same interest. If you have any suggestions, please let me know. Kudos!

I found your blog site on google and examine just a few of your early posts. Proceed to keep up the superb operate. I just additional up your RSS feed to my MSN Information Reader. Seeking ahead to studying more from you later on!?

One more important aspect is that if you are a senior, travel insurance intended for pensioners is something you should really consider. The older you are, a lot more at risk you will be for having something poor happen to you while in another country. If you are never covered by many comprehensive insurance policies, you could have many serious problems. Thanks for giving your good tips on this website.

I am not sure where you’re getting your info, but great topic. I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more. Thanks for wonderful information I was looking for this information for my mission.

fantastic issues altogether, you just won a brand new reader. What may you suggest in regards to your post that you made a few days ago? Any sure?

Oh my goodness! an amazing article dude. Thank you However I am experiencing situation with ur rss . Don?t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody getting equivalent rss downside? Anyone who knows kindly respond. Thnkx

Hello, I enjoy reading through your article post.

I wanted to write a little comment to support

you.

Spot on with this write-up, I really assume this website wants far more consideration. I?ll in all probability be again to read far more, thanks for that info.

This post is a testament to your expertise and hard work. Thank you!

Thanks for your article on this blog. From my own experience, there are occassions when softening up a photograph may well provide the wedding photographer with a little an creative flare. Many times however, this soft blur isn’t exactly what you had under consideration and can often times spoil a normally good photo, especially if you intend on enlarging them.

Excellent post. I was checking continuously this blog and I’m impressed! Very useful info particularly the last part 🙂 I care for such information much. I was looking for this certain information for a long time. Thank you and good luck.

Heya i am for the first time here. I found this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and aid others like you aided me.

I do consider all the ideas you have introduced for your post. They are very convincing and can definitely work. Still, the posts are very quick for novices. Could you please extend them a bit from subsequent time? Thanks for the post.

Thanks for your article. I would love to comment that the very first thing you will need to accomplish is find out if you really need credit repair. To do that you will need to get your hands on a copy of your credit rating. That should not be difficult, because the government necessitates that you are allowed to obtain one totally free copy of your own credit report every year. You just have to check with the right persons. You can either look into the website for your Federal Trade Commission as well as contact one of the leading credit agencies right away.

very good submit, i actually love this website, keep on it

This article was a delightful enjoy reading. Your passion is clearly visible!

Your post resonated with me on many levels. Thank you for writing it!

worldwide pharmacy online overseas online pharmacy – best rated canadian pharmacy

Купить диплом в уфе – Это получить официальный удостоверение по среднем учении. Свидетельство обеспечивает вход в обширному ассортименту профессиональных и образовательных возможностей.

This post is packed with useful insights. Thanks for sharing your knowledge!

This article was a delightful enjoy reading. Your passion is clearly visible!

I’m in awe of the way you handle topics with both grace and authority.

In accordance with my study, after a in foreclosure home is sold at an auction, it is common for any borrower to be able to still have a remaining balance on the loan. There are many creditors who seek to have all charges and liens paid by the future buyer. Having said that, depending on specified programs, regulations, and state legal guidelines there may be several loans that aren’t easily resolved through the transfer of financial products. Therefore, the obligation still remains on the debtor that has received his or her property in foreclosure process. Many thanks for sharing your notions on this site.

It?s actually a cool and useful piece of info. I?m happy that you simply shared this useful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

What?s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It positively helpful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & aid other users like its aided me. Good job.

Hiya, I am really glad I have found this information. Nowadays bloggers publish just about gossips and net and this is actually irritating. A good web site with exciting content, this is what I need. Thank you for keeping this website, I will be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can not find it.

Hey there! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any suggestions?

Your post resonated with me on many levels. Thank you for writing it!

Hey! I know this is kinda off topic nevertheless I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My site discusses a lot of the same subjects as yours and I feel we could greatly benefit from each other. If you happen to be interested feel free to send me an e-mail. I look forward to hearing from you! Awesome blog by the way!

Hey There. I found your blog the use of msn. That is an extremely well written article. I will make sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your helpful information. Thank you for the post. I?ll certainly return.

I have learned some new points from your internet site about computer systems. Another thing I’ve always thought is that laptop computers have become something that each family must have for many people reasons. They provide convenient ways to organize the home, pay bills, shop, study, listen to music and even watch tv programs. An innovative method to complete many of these tasks is with a laptop computer. These computers are mobile ones, small, strong and easily transportable.

Yet another thing is that while searching for a good internet electronics retail outlet, look for online stores that are frequently updated, keeping up-to-date with the latest products, the top deals, in addition to helpful information on products. This will make certain you are dealing with a shop which stays ahead of the competition and gives you what you ought to make educated, well-informed electronics purchases. Thanks for the crucial tips I’ve learned from your blog.

I’m extremely impressed together with your writing skills as neatly as with the structure to your blog. Is that this a paid subject matter or did you customize it yourself? Anyway stay up the nice high quality writing, it is rare to look a nice blog like this one nowadays..

We are offering Concrete Parking Lot Contractor, Concrete Installation Contractor Service, warehouse flooring, commercial, and industrial concrete roadways.

I have been surfing on-line more than three hours these days, yet I by no means found any attention-grabbing article like yours. It?s pretty price enough for me. In my view, if all webmasters and bloggers made good content material as you probably did, the net will probably be a lot more helpful than ever before.

We are offering Concrete Parking Lot Contractor, Concrete Installation Contractor Service, warehouse flooring, commercial, and industrial concrete roadways.

Thanks for your posting. One other thing is that if you are disposing your property by yourself, one of the difficulties you need to be alert to upfront is just how to deal with home inspection reviews. As a FSBO retailer, the key about successfully shifting your property in addition to saving money about real estate agent income is expertise. The more you know, the more stable your sales effort will be. One area exactly where this is particularly critical is home inspections.

Hi! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a group of volunteers and starting a new project in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us valuable information to work on. You have done a marvellous job!

Great paintings! This is the type of info that should be shared around the internet. Disgrace on Google for no longer positioning this submit higher! Come on over and consult with my web site . Thanks =)

I feel this is one of the such a lot important information for me. And i am happy studying your article. But should commentary on some common things, The web site taste is great, the articles is actually excellent : D. Just right task, cheers

Your webpage does not render appropriately on my blackberry – you may wanna try and repair that

This was a great enjoy reading—thought-provoking and informative. Thank you!

Attractive section of content. I just stumbled upon your website and in accession capital to assert that I acquire actually enjoyed account your blog posts. Any way I will be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you access consistently rapidly.

Your passion for this subject shines through your words. Inspiring!

Wonderful web site. A lot of useful info here. I am sending it to a few friends ans also sharing in delicious. And of course, thanks for your sweat!

Thanks for your write-up. I would also like to opinion that the first thing you will need to conduct is verify if you really need credit restoration. To do that you simply must get your hands on a duplicate of your credit report. That should never be difficult, ever since the government necessitates that you are allowed to receive one totally free copy of your own credit report every year. You just have to request the right folks. You can either look at website for your Federal Trade Commission or even contact one of the leading credit agencies instantly.

Thanks, I’ve recently been searching for information about this subject for ages and yours is the best I’ve discovered so far.

This design is spectacular! You certainly know how to keep a reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Great job. I really loved what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

Thanks a lot for the helpful content. It is also my belief that mesothelioma has an incredibly long latency period of time, which means that signs of the disease won’t emerge till 30 to 50 years after the original exposure to mesothelioma. Pleural mesothelioma, which can be the most common type and has an effect on the area within the lungs, will cause shortness of breath, breasts pains, including a persistent coughing, which may result in coughing up body.

Today, I went to the beach with my kids. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She put the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is entirely off topic but I had to tell someone!

Thanks for this article. I’d also like to say that it can become hard if you find yourself in school and starting out to initiate a long credit rating. There are many pupils who are merely trying to pull through and have a protracted or beneficial credit history can occasionally be a difficult factor to have.

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you could do with some pics to drive the message home a little bit, but other than that, this is excellent blog. A fantastic read. I will definitely be back.

Nice i really enjoyed reading your blogs. Keep on posting. Thanks

I beloved as much as you’ll obtain performed proper here. The comic strip is tasteful, your authored material stylish. nonetheless, you command get got an edginess over that you want be turning in the following. ill certainly come more previously once more as precisely the similar nearly very often inside case you protect this increase.

Spot on with this write-up, I really suppose this web site needs rather more consideration. I?ll most likely be once more to read way more, thanks for that info.

Can I just say what a aid to find someone who really knows what theyre talking about on the internet. You definitely know the way to bring an issue to light and make it important. More individuals need to learn this and understand this side of the story. I cant believe youre no more common because you definitely have the gift.

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your posts as long as I provide credit and sources back to your blog? My blog site is in the exact same niche as yours and my visitors would really benefit from some of the information you present here. Please let me know if this okay with you. Cheers!

My brother suggested I might like this web site. He was entirely right. This post actually made my day. You can not imagine simply how much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!

Thank you for another informative web site. Where else could I get that type of info written in such a perfect way? I’ve a project that I’m just now working on, and I have been on the look out for such info.

hey there and thanks for your info ? I have certainly picked up anything new from right here. I did then again expertise several technical issues using this site, since I skilled to reload the site many times prior to I may just get it to load correctly. I had been pondering if your web hosting is OK? No longer that I’m complaining, but slow loading instances occasions will often affect your placement in google and could damage your high-quality ranking if advertising and ***********|advertising|advertising|advertising and *********** with Adwords. Anyway I am including this RSS to my e-mail and can look out for much extra of your respective intriguing content. Ensure that you update this again soon..

Hello, i think that i noticed you visited my site so i came to ?return the desire?.I am attempting to to find issues to improve my web site!I assume its adequate to use a few of your ideas!!

Greetings from Carolina! I’m bored to tears at work so I decided to browse your blog on my iphone during lunch break. I really like the knowledge you present here and can’t wait to take a look when I get home. I’m amazed at how fast your blog loaded on my mobile .. I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways, wonderful blog!

It is appropriate time to make some plans for the future and it is time to be happy. I’ve read this post and if I could I wish to suggest you some interesting things or suggestions. Maybe you can write next articles referring to this article. I wish to read more things about it!

It is my belief that mesothelioma is usually the most dangerous cancer. It has unusual properties. The more I actually look at it the greater I am persuaded it does not react like a true solid human cancer. In the event mesothelioma is actually a rogue virus-like infection, then there is the chance of developing a vaccine along with offering vaccination for asbestos exposed people who are vulnerable to high risk associated with developing upcoming asbestos linked malignancies. Thanks for revealing your ideas on this important health issue.

Also a thing to mention is that an online business administration study course is designed for people to be able to easily proceed to bachelors degree programs. The Ninety credit certification meets the other bachelor college degree requirements then when you earn your current associate of arts in BA online, you may have access to up to date technologies with this field. Several reasons why students are able to get their associate degree in business is because they’re interested in the field and want to get the general education necessary ahead of jumping in a bachelor diploma program. Many thanks for the tips you actually provide with your blog.

I have learned newer and more effective things out of your blog post. Yet another thing to I have discovered is that in many instances, FSBO sellers will certainly reject people. Remember, they’d prefer to never use your companies. But if an individual maintain a comfortable, professional relationship, offering support and staying in contact for around four to five weeks, you will usually have the capacity to win a meeting. From there, a house listing follows. Many thanks

A great post without any doubt.

Hello! I know this is kinda off topic nevertheless I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest writing a blog article or vice-versa? My site covers a lot of the same subjects as yours and I believe we could greatly benefit from each other. If you might be interested feel free to send me an e-mail. I look forward to hearing from you! Great blog by the way!

Thanks for your text. I would love to say that the health insurance broker also utilizes the benefit of the particular coordinators of your group insurance coverage. The health broker is given a long list of benefits wanted by anyone or a group coordinator. What any broker does indeed is search for individuals or even coordinators which best complement those demands. Then he provides his referrals and if both parties agree, the broker formulates an agreement between the 2 parties.

Thanks for the helpful content. It is also my belief that mesothelioma cancer has an extremely long latency interval, which means that symptoms of the disease might not exactly emerge until finally 30 to 50 years after the original exposure to asbestos. Pleural mesothelioma, which can be the most common kind and impacts the area within the lungs, might result in shortness of breath, chest pains, plus a persistent cough, which may produce coughing up blood vessels.

Heya i?m for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and help others like you aided me.

Nice i really enjoyed reading your blogs. Keep on posting. Thanks

Thanks for another magnificent post. Where else could anyone get that kind of info in such an ideal way of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I’m on the look for such info.

After examine just a few of the blog posts in your web site now, and I really like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website checklist and will likely be checking again soon. Pls check out my website as effectively and let me know what you think.

Heya i?m for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It truly useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and aid others like you aided me.

I like the valuable information you supply in your articles. I?ll bookmark your weblog and check again here frequently. I’m reasonably sure I?ll be informed many new stuff proper right here! Best of luck for the next!

I might also like to state that most individuals that find themselves devoid of health insurance are generally students, self-employed and those that are not working. More than half of those uninsured are under the age of Thirty-five. They do not think they are wanting health insurance since they’re young plus healthy. The income is often spent on homes, food, in addition to entertainment. Some people that do represent the working class either complete or part time are not presented insurance by way of their work so they get along without due to the rising expense of health insurance in america. Thanks for the thoughts you talk about through this website.

I discovered more new things on this weight loss issue. A single issue is a good nutrition is vital whenever dieting. An enormous reduction in junk food, sugary food, fried foods, sugary foods, red meat, and bright flour products could possibly be necessary. Possessing wastes unwanted organisms, and wastes may prevent desired goals for fat loss. While certain drugs temporarily solve the situation, the horrible side effects are usually not worth it, and they also never offer you more than a short-lived solution. It’s a known indisputable fact that 95 of fad diets fail. Thank you for sharing your ideas on this blog site.